Jean-Yves Le Bars became a lighthouse keeper in 1979, prior to what, he had been working in Brest as a ship repairer and was a volunteer with the SNSM lifeboat service, where he carried out rescues and gave lessons in mechanics. As a student, he had already worked in lighthouses as a summer job. At the time of the oil crisis, in 1976, following lay-offs in the ship repair industry, he was made redundant and decided to apply to be a full-time lighthouse keeper. He passed the competitive examination to attend the Ecole des Phares in Brest and was admitted to the Lighthouse and Beacon Operation and Intervention Centre in Brest.

- Now that I'm retired, I realize that I was part of a heritage of post-war maritime life. The first lighthouse where I worked, was in Saint-Mathieu. The site was fascinating and also, as we had to take care of the Lochrist lighthouse and the small sector lighthouse in the abbey, we had the best hands-on training possible.

The abbey and the lighthouse of Saint-Mathieu

© Photo Armand Breton, coll. Les Amis de St-Mathieu

Then I went to Les Pierres Noires, to Ar-Men and finally Le Four. At first, I was a trainee and after a year I became a fully-fledged member and joined the Trade Unions.

The staff changeover of lighthouses at sea was prepared the day before. Everything that was needed was put into boxes or bags : meat, bread, a change of clothes and also personal items. Then it was off to the port of embarkation : Le Conquet, Argenton, Audierne or L'Aber Wrac'h. And finally on board the lighthouse tender. On Tuesdays, it was the turn of Ar-Men and La Vieille, on Wednesdays it was Les Pierres Noires and Le Four, on Thursdays Kéréon and La Jument and on Fridays it was L'Ile Vierge.

The lighthouse keeper lobbed the towline monkey's fist over to the boat to start the wheels in motion for the relief.

© Photo Wikipedia

In France, the "touline" ( from the British word towline ) is a lightweight rope,

one end of which is attached to a large tow line or heaving line, mooring or backhaul line.

The other end is terminated by a towline knob often called a monkey's fist,

a spherical knot in the shape of a fist designed to make it easier to grip for launching.

On this gun tampion, decorative emblem of the Lighthouses and Beacons,

appear a towline and its towline knob, symbolizing relief at sea.

Then we installed the cartahu, the back-and-forth pulley system which was operated manually from the lighthouse winch. The equipment was winched up first and after the men in order of seniority.

At Ar-Men, you never knew when you were going up ! Sometimes we would leave Brest on Monday and transit via the Island of Sein to see if were possible to reach the lighthouse. Occasionally we got stuck in bad weather. The lighthouse tender could not close to the lighthouse and we could not leave if we were on watch. I saw some colleagues go to Ar-Men for a fortnight and end up staying there for a month because the relief was not possible. At Les Pierres Noires, if the tide was higher than 70, the platform at the base of the lighthouse was submerged and we could not take in fresh supplies. I remember being stuck there with two maintenance workers and we had no food. From the lighthouse, we let a buoy drift into the current and the boat's deckhand hung a waterproof bag with fresh bread and a few titbits to eat over it so that we could haul in some food.

When we had the helicopter drops, everything changed. I had already done some helicopter air drops when I was in the army and also with the SNSM. I remember a relief at Les Pierres Noires during a force seven. I went to Le Conquet and with all my gear ready in boxes for my shift. The sea was so rough that the lighthouse tender couldn't come and I was sent home to Brest. Later the same day, the engineer called me at 3pm to say change of plan, we are going to airlift you in ! I was picked up from home, driven to the air base and flown to the lighthouse in a Dauphin helicopter. Flying over the sea between Le Conquet and Les Pierres Noires, during the storm, it was incredible, everything was white as snow.

The guardians were not against airdrops, however we asked to have harnesses rather than simple straps, and an air lift pay bonus ! After this was established with the bosses. I must have done a total of about 50 air drops.

While on watch, we also monitored other lighthouses and buoys in our area. We had to do fire watches at 11p.m, 1a.m, and 4a.m. Kéréon was electric, thanks to a wind generator coupled to a wind turbine. La Jument was oil powered with an electric rotation system. Monitoring the oil fire required regular visits to the fire pit. Its lighting was a special, magical moment. At Ar-Men, the two keepers worked together to ignite the fire and it took twenty minutes of preparation. We had two white spirit lamps to preheat the fire. Afterwards, we used a compressed air bottle to pressure up the oil and a preheater to prime the spirit lamps. The bright flame was provided by an asbestos mantle like the ones on camping-gas lamps, but far bigger. A small outlet allowed the oil to evaporate completely. If it stopped evaporating, the oil could flow directly into the generator, which could cause a burner fire or even worse blacken the whole lantern and burst the lens ! So, we always had to keep an eye on the manometer to check the pressure. Once, I had a burner fire but I got there in the nick of time and put it out. In case of a problem, we always had backup equipment and as a last resort, an emergency lamp called the Aladdin lamp that was placed at the focus point of the lens if things came to worse.

The Aladdin lamp is a large oil lamp with a special asbestos mantle

The lihthouses are a marvellous heritage

Based on © Aladdin Animated film

- Yes, but it was only 50% of the power and we had only 20 minutes to fix the problem...

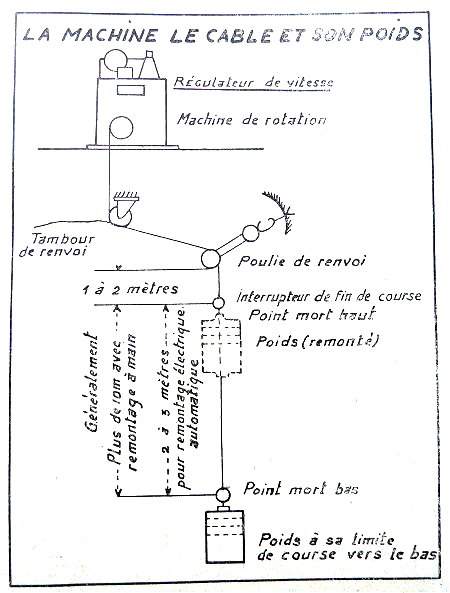

In the lights not yet converted to electricity, the lens rotation was ensured by a system of gears with a differential and regulator, driven by a weight relaying on gravity going down the tower to which the keeper had to ascend and descend throughout the operation to wind it up.

The regulator, the cable and its weight

Handbook for the electromechanic and the lighthouse keeper - Lighthouses and Beacons 1956

It was also necessary to control the speed regulator so that the rotation of the lens stayed in synch with the flash and occultations. Each lighthouse has its own rhythm & timing.

The rhythm must always be exact, it must never vary

Handbook for the electromechanic and the lighthouse keeper - Lighthouses and Beacons 1956

When it was foggy and you couldn't see certain landmarks, you had to sound the foghorn. Two compressors, one main and one back-up, supplied air to a tank that drove an electric motor to sound a large horn. Each lighthouse had a sound signal with a unique rhythm. We had to use a stopwatch to check the timing. However, if we opened a window, the temperature would change and the rhythm would have to be re-adjusted. With automation, the sound signal was no longer necessary.

Living on a lighthouse could be Paradise or Hell. It all depended on the team. I've seen teams who never got on. I've seen guardians making faces at each other not eating together just to see who would give in first. When I was at Ar-Men, I had a good group of friends and I liked to go there even though it's a lighthouse that's known to be hard. At Le Four, with my colleague, we had great meals together. Oh, the gorillas ! This guy had a brother at catering school and he had plenty of top recipes. It must be said that in the lighthouses, eating well was the secret to survival.

We alternated meat or fish. Fish were caught in the autumn and spring, when we had time to spare and salted to preserve them. At that time there was no fridge or freezer. The salted conger was excellent.

But there were some lighthouses that were better for fishing than others. La Vieille, for example, was the best. We could catch pollock of 2 or 3 kg. At Kéréon and Le Four, we had an old and patched up lobster pot that we lowered into a lobster hole. Each time was a winner.

With everything going electronic, we could see that things were inevitably going to change. Other companies had stronger trade unions and I felt that there was a lack of protection by our trade unions compared to what I had experienced in the ship repair world, where the unions made a difference to the quality of daily life for the workers. At Les Phares et Balises, the management of the staff was administrative and with just a C.A.P. for transfers and discipline, in which the elected staff representatives were members of the two unions.

At this time, for the lighthouse keepers, the general secretary of the CGT trade union was based in a lighthouse near Lorient. Another manager was based in Cherbourg and they asked me to join them in the office. We could already see that automation was inevitable. Our first congress was held in Brest. And I found great support from my fellow former merchant mariners. Our demands concerned not only wages, but also living conditions, participation in the choice of lighthouses that were to be automated and, above all, the retraining of personnel affected by this choice. At the union, I was part of these negotiations.

In 1986, the idea we had, since we could not put out our lights and would never do so, was to get the general public interested by doing a sound and light show. Turn on the sound signals and lights during the day and night and alert the media. The Fédération de l'Equipement agreed to give us good media coverage. Every night we did a radio session.

The administration responded well.

As a result of this movement, which lasted two weeks, we obtained category B. And we were sent to film the conditions in the lighthouses. After our sound and light show they installed sanitary facilities everywhere. And we had access to training in electronics in Nantes. We were also able to negotiate the order of automation of the lighthouses. We started to automate not the shore lights, but the ones where the conditions were hardest, Ar-Men and La Jument.

In Kéréon, in 1989, the lighthouse was badly damaged by a fierce storm. Everything had been damaged : all the furniture had been ripped apart by the water that had entered through the kitchen. Portholes and windows had been shattered, water poured down three flights of stairs, the supply winch was twisted beyond repair. They really took a beating. And yet, it was those guys from Kereon, who were most opposed to automation. They wanted to maintain the tradition of this iconic lighthouse.

Kéréon, a palace in Hell

© Photo Le Chasse-Marée

The change over to automation was done too quickly in my opinion. In Cherbourg or La Hague, it took much longer : about five years per lighthouse. If the automation had been longer, it would have been easier to retrain get the guys into other jobs in the company. There were just too many back in the office.

The future of lighthouses is another story. A page was turned. My work will never happen again. But there is one thing I have noticed. It's that the whole system was based on a duty of public service. And even more. Above all, it was a valuable lifesaving aid for the sailors. A mission to save lives, not just a simple vocation. There was a very strong sense of pride around that. I know colleagues who spent a whole night turning the lens by hand when all else failed.

Throughout my career, I have found my shipmates to be conscientious people who were always concerned about maritime safety. Although the members of this corp, of which I was one of the last representatives, had not experienced the harsh conditions of our elders, they shared the same fighting spirit.

Lighthouse keepers were good men, men of duty.

Thanks to Glyn Orpwood and Andrew Chudley

who reread this text and modified the English version.

-----------------------------------