What could be more natural for the human species that populates the whole surface of the Earth than to base its notion of time on the course of the Sun? If we lived in the sea, it is likely that we would have chosen to base our time on the rhythm of the tides. Today, our knowledge, our technical progress, the development of transport and globalization have led us to adopt a different and very scientific time measurement. So, the solar time of our elders is now part of our heritage.

Dating from Antiquity, sundials are fixed, thus linked to a specific geographical location.

This simple observation contains several obvious facts that lead us to think about some interesting points:

The notion of time has evolved since ancient times.

It was the Egyptians who first, around 1500 BC, had the idea of dividing the day in 12 hours and as much for the night. The first known sundial dates back to that time when the hours, depending on the season, were unequal. So we haven't always had the same requirement in terms of time. Today, we live by the minute and the second. Programs, shows, meetings must start on time. The craftsman bills his time. This requirement, which stems from technical inventions, only became widespread in the twentieth century. It was not the same in the past, and the old sundials bear witness to a time when more or less was tolerated because it was enough.

Therfore, old dials are not perfectly accurate.

The sundials depend on the sun.

They do not work at night or overcast. In addition, their design requires knowledge in astronomy.

Unlike a watch or a clock, which indicates a time, the sundial measures an angle: the hour angle of the sun, which is read as if it was a time.

By reading it, one states the 'true solar hour' of the place where the dial is.

From true solar time to legal time.

Things get complicated when we want to turn this real solar time into legal time, the one that today manages our daily actions.

The longitude offset:

The legal time imposed in France is, by convention, that of the Greenwich meridian increased by one hour. An extra hour is added in the summer.

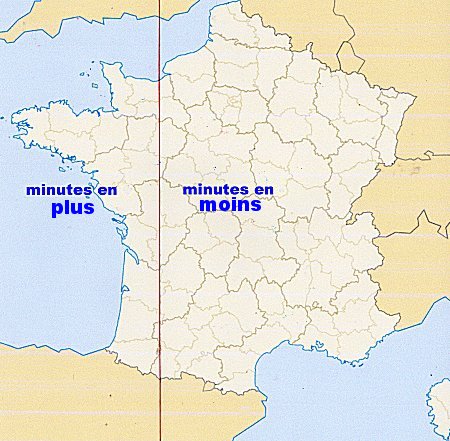

Since a sundial is not necessarily located on the Greenwich meridian, a correction must be made to take its geographical position into account. And it's not nothing: during a live report, one evening in August, on television, all Bretons can realize that it is already dark in Paris while it is still light behind their Windows. For example, solar time has 50 minutes difference between Strasburg and Brest. This is called the "longitude offset". It amounts to 4 minutes per degree of longitude: minutes less at east of the Greenwich meridian, or in addition if one is to the west, as in Brittany.

So it's not very simple.

The Greenwich meridian crosses France from north to south

along a line that passes between Caen and Le Havre,

Angers and Le Mans, Niort and Poitiers, Bordeaux and Bergerac,

and crosses the Pyrenees mountains at the Gavarnie circus.

The equation of time:

To this is added a much more complicated correction due to two astronomical causes discovered as early as the 2nd century by Ptolemy the Greek:

-

The sun, which seems to move on the celestial equator, rather moves on the ecliptic plane. Basically, its apparent path is not round, but a little oval. In reality, it is the Earth that revolves around the Sun, but this was not known at the time of Ptolemy.

-

Then, it should be noted that the distance between the Earth and the Sun varies continuously throughout the year. So it is the same with the force of attraction exerted by our star. The result for our northern hemisphere is that the Earth moves faster in winter than in summer.

Astronomers have added these two causes and established an equation, called the 'equation of time'. It gives in minutes and tenths of a minute the positive or negative correction to be made to the solar hour for each day of the year.

But let's speak Pierre Labat-Ségalen, one of the authors of the book indicated below. He has controlled and completed all the pages of this website concerning the sundials :

"The following tables indicate the correction to be made in minutes for the 1st, 10th, 20th and 30th of the month.

|

Day of the month |

January |

February |

March |

April |

May |

June |

| 1 |

+3,4 |

+13,6 |

+12,5 |

+4,1 |

-2,8 |

-2,3 |

| 10 |

+7,3 |

+14,3 |

+10,5 |

+1,5 |

-3,6 |

-0,8 |

| 20 |

+10,9 |

+13,8 |

+7,7 |

-0,9 |

-3,6 |

+1,3 |

| 30 |

+13,3 |

0 |

+4,7 |

-2,7 |

-2,6 |

+3,4 |

|

Day of the month |

July |

August |

September |

October |

November |

December |

| 1 |

+3,6 |

+6,3 |

+0,2 |

-10,1 |

-16,3 |

-11,2 |

| 10 |

+5,2 |

+5,4 |

-2,8 |

-12,8 |

-16,1 |

-7,5 |

| 20 |

+6,2 |

+3,5 |

-6,4 |

-15,1 |

-14,5 |

-2,7 |

| 30 |

+6,4 |

+0,8 |

-9,8 |

-16,3 |

-11,5 |

+2,3 |

Here are 2 examples for LANILDUT, West longitude 4°44'45, then approximately 4.75 degrees.

*

On March 10 you read 11 on the sundial.

The legal time will be:

11 h

+ 1 h of imposed delay.

+ 19 minutes of longitude offset ( 4 x 4,75 = 19 )

+ 10.5 minutes of correction from the equation of time on March 10.

It will therefore be 12:30 in legal time.

*

On September 30 you read 13 at the sundial.

The legal time will be:

13 h

+ 2 hours of imposed delay: 1 imposed hour + 1 summer hour

+ 19 minutes of longitude offset : 4 x 4.75 = 19

minus 10 minutes of correction from the equation of time on September 30.

So it will be 15:09. »

Pierre Labat-Ségalen

Works of art

Sundials only need a style and a flat support in a semicircle to be operational. If this support is a square or rectangular slab, it remains an important space that the dial makers often occupied. From then on, coats of arms, various maxims, pious engravings or craftsman's name illustrate this small heritage in different ways and constitute true works of art that we will always appreciate to decipher.

So let us no longer pass in front of a sundial without stopping there: it is silent, but it has so much to tell us!

READ MORE

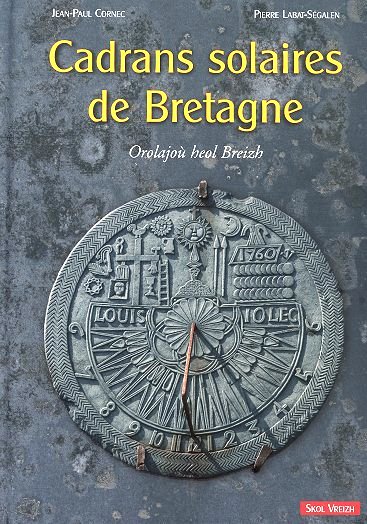

We recommend reading the book below

by Pierre LABAT-SEGALEN

and Jean-Paul CORNEC

Skol Vreizh Ed., 2010

Skol Vreizh Ed., 2010

cardboard cover,

192 pages in 21x30 cm format

The authors of this book, passionate about gnomonics (the science of sundials), have for years, municipality by municipality, traveled the five historical departments of Brittany to deliver in this book abundantly illustrated an inventory as completely as possible of the sundials of Brittany.

The reader will find abundant explanations, much more detailed than those appearing on this page, as well as a large amount of color photographs showing the extraordinary variety offered by this little heritage still too little known to the general public.

And to complete this book, read also on the internet

Yves-Pascal Castel's study.

Yannick Loukianoff