As has often happened, the heritage of the Iroise Country is not entirely in its original region. Sometimes you have to travel tens or even hundreds of kilometres to discover one of its elements. Over the years, objects have been moved to be, for example, held in distant private collections or exhibited in museums. Not to mention the thefts, such as that of the Virgin with the fig, disappeared from the chapel N.D. du Val in Trébabu in 1977 and found in Provence 28 years later, or that of the sundial of the church of Tréouergat that we are still looking for.

In Rennes, you can admire at the Museum of Brittany a very old coin, since it dates back to the 4th century BC. Its discovery dates back to 1959 and its tribulations, which we tell you here, are really not mundane.

In Rennes, you can admire at the Museum of Brittany a very old coin, since it dates back to the 4th century BC. Its discovery dates back to 1959 and its tribulations, which we tell you here, are really not mundane.

Plug in the sound and find here the story of the golden statere of Pytheas

as well as many other elements of our heritage on the website Voix du Patrimoine.

A recent storm had accumulated there a thickness of about one meter of laminaries that were beginning to rot. The sailor fills a few bags in order to spread them as fertilizer in his garden in Brest.

A few weeks later, as the seaweeds had partially decomposed, he saw a bright object among his salads.

Stuck between the thick cleats of a rough laminar, a beautiful gold coin shone in the sun.

YL Photo: Reenactment

A vigorous brushing under the tap overcame the algae debris that had encrusted it, which proved that the gold coin had indeed been brought by the sea and not lost by a walker. The officer logically concluded that it came from the sinking of a ship not far from Lampaul-Ploudalmézeau1.

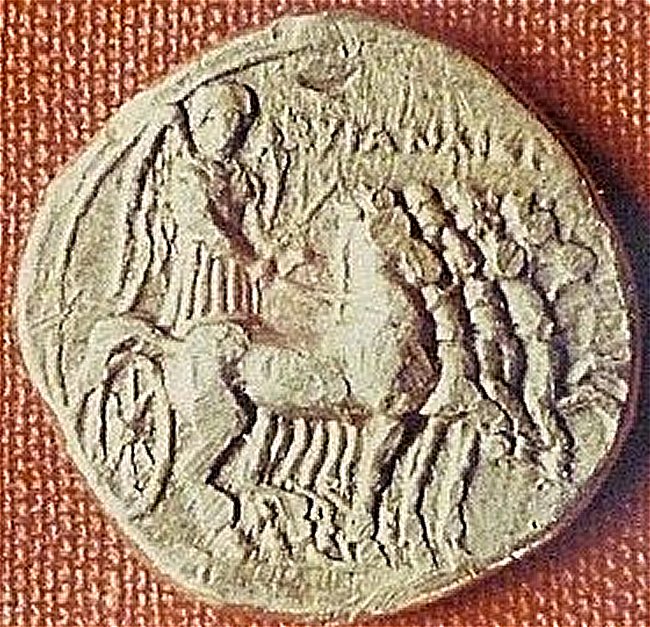

On one side, the coin depicted an ill figure standing on a chariot pulled by four horses surmounted by an almost illegible inscription.

On the other side, a crowned figure, half-naked, held a kind of spear along which was another inscription.

There is no doubt that it was an ancient currency. To find out more, it had to be assessed.

In February 1960, the sailor addressed the Faculty of Letters in Rennes and contacted Pierre-Roland Giot, director of the Prehistoric Antiquities District. The latter entrusted the object for identification to Jean-Baptiste Colbert de Beaulieu, a numismatist scholar, who readlessly recognized a stater from the Greek colony of Cyrene, present-day Libya, and struck only a few years after the death of Alexander the Tall, between 322 and 313 BC. Right : a quadrige led by the winged goddess Nike

( the Victory of Samothrace )

and the Name in Greek of the Cyreneans. Back : Zeus of Cyrene ( Zeus-Ammon ) makes a libation with the help of a phial and leaning on a scepter. You could read the name of Polianthès, monetary magistrate of Cyrene in -322. The pure gold coin, roughly round, had a diameter of about 2 cm. It weighed 8.54 grams and was part of a series well known to collectors.

Jean Bousquet, the new director of the District of historical Antiquities of Brittany and Country of the Loire, negotiated the acquisition of the coin and the Laboratory of Archaeology of the Rennes' Faculty of Letters became legally its owner.

The stater, so scrupulously studied, was the subject of several publications2 in the specialized press because it was of very special importance.

Indeed, from the outset, archaeologists suspected that it may have belonged to the expedition of Pythéas3, the bold Navigator of Marseille whose writings had disappeared and whom Latin historians had considered as an affabulator.

Although it could not be formal proof of this, the discovery made this ancient expedition very plausible and rehabilitated the navigator.

The gold coin was kept in Rennes and, for about fifty years, was completely forgotten. The protagonists of his discovery disappeared one after the other. Publications remained, but at the Archaeology Laboratory no one knew where this important part of our heritage had been stored.

Mystery...

The golden stater of Pytheas had disappeared like its discoverers, and its beautiful story seemed to end there...

No doubt, the currency on the photo corresponded in every way to the Pytheas's stater. This one was no longer in the Faculty's premises, but was now part of a private collection !

And the sale was supposed to take place two days later !

Without further ado, the teacher alerted the Museum of Brittany. Under the leadership of its Curator of Heritage in charge of numismatics, the Regional Archaeology Service obtained in extremis that the currency of Cyrene be withdrawn from sale and entrusted to this museum.

The so-called gold coin of Pytheas was saved a second time.

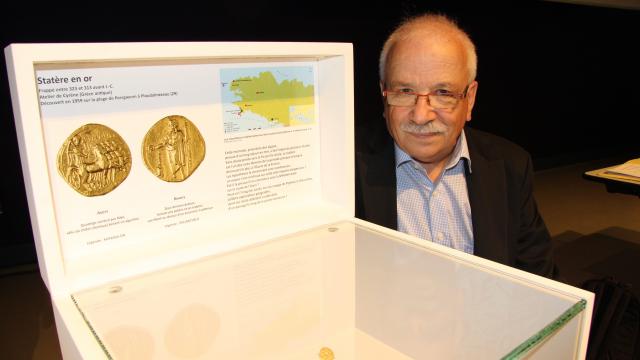

It is now presented to the public in a showcase dedicated to it. As the museum's collections are inalienable, we can only hope that they will satisfy the curiosity of visitors for a long time.

In the Musée de Bretagne: The showcase of the golden stater

and the numismate who saved it a second time

Photo Ouest-France 21 June 2015

1- Rather than imagining a shipwreck, it is easier to think that a purse or a small box of gold coins could have fallen into the water during a transfer on a canoe in order to buy food or tin from local people ashore.

2- See the article by P.R. Giot and J.B. Colbert de Beaulieu published in 1961 in the Bulletin of the Prehistoric Society of France, the report of Jean Bousquet published the same year in the Annals of Brittany, and the account made by the same author during the session of October 14, 1960 of the Academy of Inscriptions and Beautiful Letters.

3- To complete this story, see the page of this site entitled Pytheas the Massaliote, written by Georges Tanneau.