Access :

Leave St-Renan by the road to Plouarzel ( D5) and when you reach Plouarzel turn right at the roundabout towards Lampaul-Plouarzel. Cross this town and at the fork, turn left towards Porspaul, the port of this municipality. When you arrive, take the small road on the right, heading towards the campsite and the Beg ar Vir headland. Park near the second bend. Two seaweed kilns are marked by wooden piles.

To the south of the road, very close to the port, a first kiln emerges from the rare dune vegetation. |

Opposite, to the north, the end of a second kiln begins to be degraded by marine erosion that causes the shoreline to retreat. |

These trenches, whose bottoms and walls are lined with flat stones, were dug into the dune over a hundred years ago by seaweed workers. At that time, as still today in Lanildut, the seaweed activity which consisted in harvesting large algae, the 'tali', generated an important resource on the whole coast of the Iroise country. But it was practiced differently 1.

Unloading of the 'tali' of the Marie-Pierre boat in C'hloc'h cove at Porspoder.

Oil on canvas by Jean-Marie Couillard. special coll.

Yves Colin, future inventor of the 'scoubidou', stands in the cart

and empties the cargo with a hook.

His father François stayed in the boat with the young Didier Bellec.

In the distance, white smoke can be distinguished from active seaweed kilns.

The long laminaria algae that characterize the underwater vegetation of the Iroise Sea as well as the rockweeds proliferating on the rocks were cut with a sickle prolonged by a long handle and brought back to the coast (

see the page of this site dedicated to these algae ).

These algae were put in millstones until they were spread out on the ground to dry them in the wind and sun.

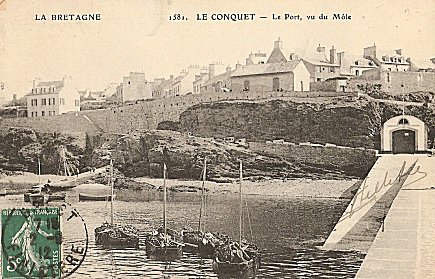

On this postcard from 1910, the seaweed boats wait for the high tide to reach the inner port of Le Conquet where they will be unloaded. © coll. JP.Clochon |

There, the algae from the millstone are spread out on the strike at the kiln where they will be burned when they will be dry. © coll. JP.Clochon |

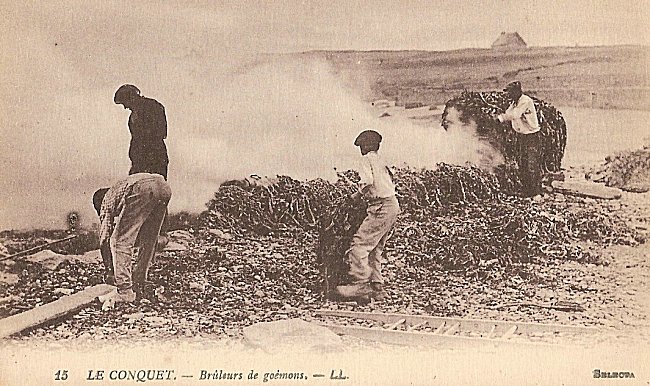

© coll. JP.Clochon

Demonstration of burning of the 'tali' at the Lanildut Algae Forum in August 2015.

When they were finally dry, the algae were placed in the kiln on a bed of burning branches. A white, pungent smoke, which stung the eyes and throat, then invaded the whole space. On some sunny days, whitish clouds were emerging from the whole coast and from the islands of the archipelago, signalling burning operations of the seaweed everywhere. At that time people coughed a lot, but nobody still talked about pollution or fine particles.

The trench is lined with flat stones at the bottom and sides.

These stones are isolated from the ground by a layer of pebbles that let air through.

Removable stone partitions separate the soda breads that will form.

The burning lasted a long time because the fire was constantly fed with new forks of dry seaweed so that the material that flowed from it filled the entire kiln. When the fire went out and the contents of the kiln had cooled, the greyish material that had solidified in the kiln was removed in pieces. These blocks were called 'soda breads'. These one could weigh 50 kg.

A soda bread presented in August 2015 at the Algae Forum in Lanildut.

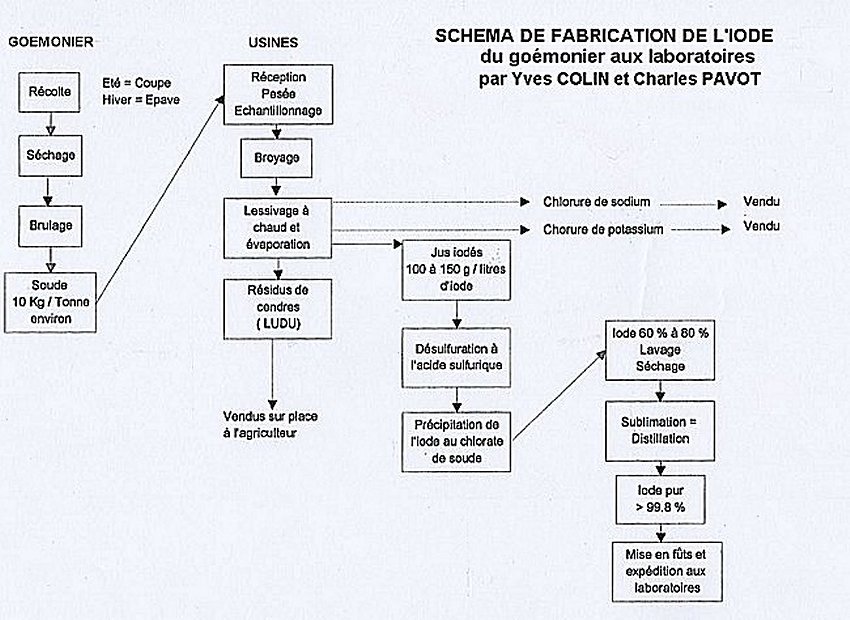

These breads, more or less regular, were weighed and analysed at the nearest iodine factory and constituted the raw material for its production: soda, iodine, potash salts which were used in particular in the chemical, pharmaceutical and glass industries. This activity took place from 1812 to 1958 with periods of high demand, iodine dye being for example the most used antiseptic during the 1914-1918 war.

This is why we observe a quantity of seaweed kilns all along the coast. Several are visible south of Porspaul, not far from Ségal Island.

Near Île Ségal, several kilns, well maintained or even restored, appear when vegetation has been cut. You can clearly see the stone slabs that line the bottom. |

|

Others are close to Lanildut Battery (

visit of the battery ).

One of them still shows, what is rare, stone partitions separating the 'lodges', which facilitated the demoulding of the soda breads.

Partitions that were often changed because the heat burst them.

This kiln with almost intact partitions, in Lanildut,

is still used during the annual seaweed festivals.

Photo JP..Clochon juillet 2015.

Lanildut: coastal path.

Several kilns still appear on private property along the Lanildut Coastal trail, not far from the battery, and in the center of the St. Lawrence Peninsula at Porspoder. It is so on all the coast of the Iroise country.

St. Lawrence Peninsula at Porspoder

Mazou, at Porspoder

In the municipality of Porspoder there is still a whole area where a large number of seaweed kilns appear in a vast expanse of grass on the seashore. Some are even of an unusual length. Others are already completely buried under the grass and we will take pleasure in looking for them and discovering them.

Come on, we'll tell you where it is, and you won't regret your trip.

On the D 27 road, in the North-South direction, 2 km after the village of Porspoder and before the port of Melon, at the place called Kervezennoc, take to the right a signposted road 'Port de Mazou'. At the end, turn left towards the hamlet of Mazou and park at the end of this road.

Important vehicles: difficult or even impossible to turn around in the hamlet of Mazou. Park before the first houses instead.

We can take a look at this charming little port (

see the page dedicated in this site ).

Follow the coastal path to the south on the left. It crosses the vast grassy area where the seaweed kilns abound.

|

|

|

|

Something very rare, we also sometimes discover near an kiln a kind of paving of large rounded pebbles. And one guesses, in the acrid white smoke of the meadow, the still burning 'soda breads' that shadows carefully deposit on these stones to let them cool slowly while another batch will soon start without loss of time. Listen, and your imagination may make you hear the heavy cracking of a fresh seaweed truck pulled painfully, in the nearby path, a horse coming up from the small port of Mazou.

But it is also often necessary to look for these ancient seaweed kilns under the herbs. Should we let them disappear into the vegetation and eventually be forgotten in the humus or sand of the dune which will perhaps preserve them for centuries to come?

|

|

These are the last witnesses of an laborious and modest activity2 which fed a whole population during more than a century and contributed to the development of our industry. These are discrete but important elements of our heritage that we must pass on to new generations for cultural reasons, but not only. Indeed, we all need temporal and social reference points. These one are concrete, numerous and well distributed in our coastal towns. This therefore deserve all our concern.

-1-

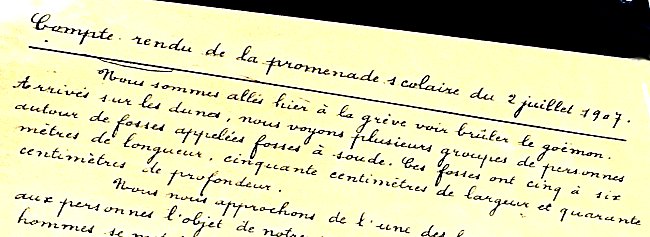

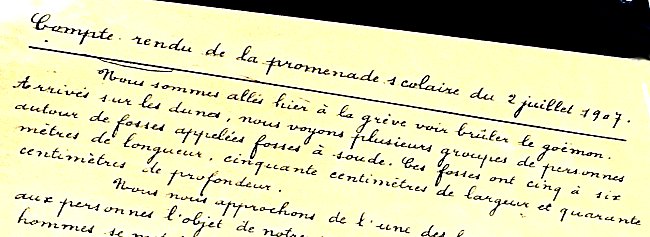

Here is the report of the visit of a class of Landéda, in 1907, at the time of the burning of the seaweed :

"We went on strike yesterday to see the seaweed burn. Arrived on the dunes, we see several groups of people around pits called soda pits. These pits are five to six metres long, fifty centimetres wide and forty centimetres deep.

We approach one of these pits and let people know the object of our walk. Lovely, one of the men is at our disposal to provide us all the desirable information.

Seaweed is collected in the sea not far from the coast using boats. The seaweed workers, armed with a sort of scythe, cut the seaweed, detach it from the Bottom, then with the help of a long-handled hoe, they lure it into their boat. When it is full, they approach the coast and unload the seaweed.

The seaweeds are transported on the dunes, using carts, wheelbarrows or stretchers. There it is spread out and turned once or twice to dry. It is piled up when it is dry. From there, carts are taken and unloaded near the soda pit.

A few twigs of wood are thrown into the pit and the fire is set on. One then takes fathoms of seaweed which one throws by handles in the pit. The seaweed burns and gives off thick smoke that obscures the horizon from all sides. As the seaweed burns, new handles are thrown into the pit and stirred with an iron-toothed fork. The seaweed gradually turns to ashes. The seaweed is no longer discarded.

In the evening, when the pit is full of ashes, the fire is extinguished and ash blocks called 'soda breads' are removed from the pit and transported either to Brignogan or to the Aber Wrac'h at the Glaizot factory where the soda is extracted. The soda breads transported to Brignogan are shipped by Mr. Glaizot to the Aber Wrac'h.

There are soda factories at Aber Wrac'h, Portsall, Le Conquet, Audierne and Pont-L'Abbé."

-2-

The seaweed activity is far from having disappeared, but it has evolved a lot with technical progress. To be convinced, it is necessary to visit the port of Lanildut and its House of Algae. Lanildut is the leading seaweed port in Europe. A whole fleet of specialized vessels land the algae taken offshore. These are then sent to factories where are manufactured alginates used as gelling agents, stabilizers, thickeners or emulsifiers for food industry..

The current seaweed boats use a "scoubidou", a kind of large mechanical hook,

to pick the laminaria of the Molène plateau. © Photo Gérard Bosch

Thanks to Jean-Pierre Clochon, historian of the Iroise country, and Marie-Hélène Colin-Maréchal, for their help and the loan of their documents.