The Abbey of Saint-Mathieu de Fine-Terre

Sanctus Mattheus of Finibus Terræ

( Municipality of Plougonvelin)

The ruins of the abbey are open and accessible at all times

GPS : 48°19'47.7 N 4°46'14.9 W

Access :

The ruins of this former abbey are located at the foot of the Pointe St-Mathieu lighthouse, halfway between Plougonvelin and Le Conquet.

Park in the parking lot next door.

Leave your vehicle in the adjacent car park. Walk along the road past the restaurant and directly opposite the hotel, take the paved alley which leads to the orientation table, the chapel and the entrance gate of the former abbey.

The remains of a vast religious complex.

This very long illustrated description of about a hundred photos is divided into 4 parts that you can obtain directly by clicking on each of the underlined numbers below the image.

-1- The old fortified fire tower that became a bell tower, whose height has been reduced by half.

-2- Location of the old buildings of the Benedictine monastery.

-3- Ruins of the abbey church.

-4- Remains of the Maurist monastery.

1- Read on this site the terrifying legend of Sainte Haude and Saint Tanguy in our page :

A legend

attributes to Saint Tanguy the founding of this abbey in the Merovingian period.

However, there are no records or remnants to prove it. In spite of this, it is probable that a first settlement, perhaps made of wood, preceded the present-day building, of which

« The Translation of the Relics of St Matthew is told in a brochure available at the Abbey Museum

another legend

claims to have housed relics of the apostle Saint Matthew from Ethiopia.

According to the historian Yves Gallet, the construction of the abbey church, now in ruins, probably began in the second quarter of the 11th century. The oldest records indicate that in 1110 the abbey was already head by

Canon Eliès : « Plougonvelin, Saint-Mathieu de Fine-Terre », Les Amis de St-Mathieu Ed., 1985.

an abbot named Daniel.

Subsequently, the building underwent alterations and in turn destruction that make the interpretation of its history somewhat complicated. But rest assured, if you are not one of those who only want a glimpse of the church, we will guide you as best we can around this jewel at the World's end.

An exquisite model of the abbey as it was in around 1500 AD is exhibited in the Abbey Museum located at the entrance. It is the result of meticulous research from the archives and greatly facilitates the understanding of the site and gives an overview of its former glory.

1/500 scale model of the abbey of Saint-Mathieu around 1500 AD, seen from the South-East.

Director: MPPA Rennes. © Photo Les Amis de St-Mathieu, Abbey Museum.

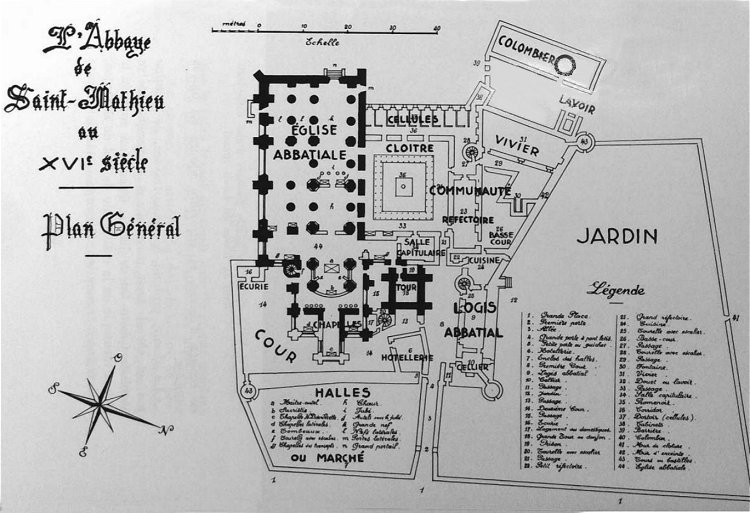

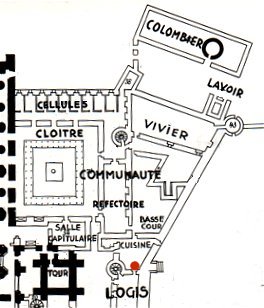

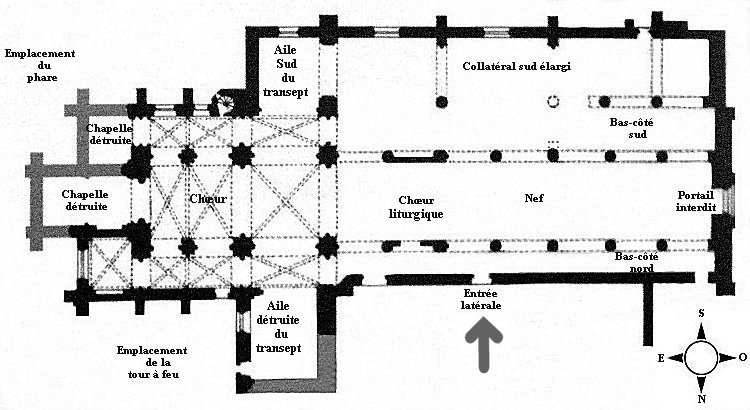

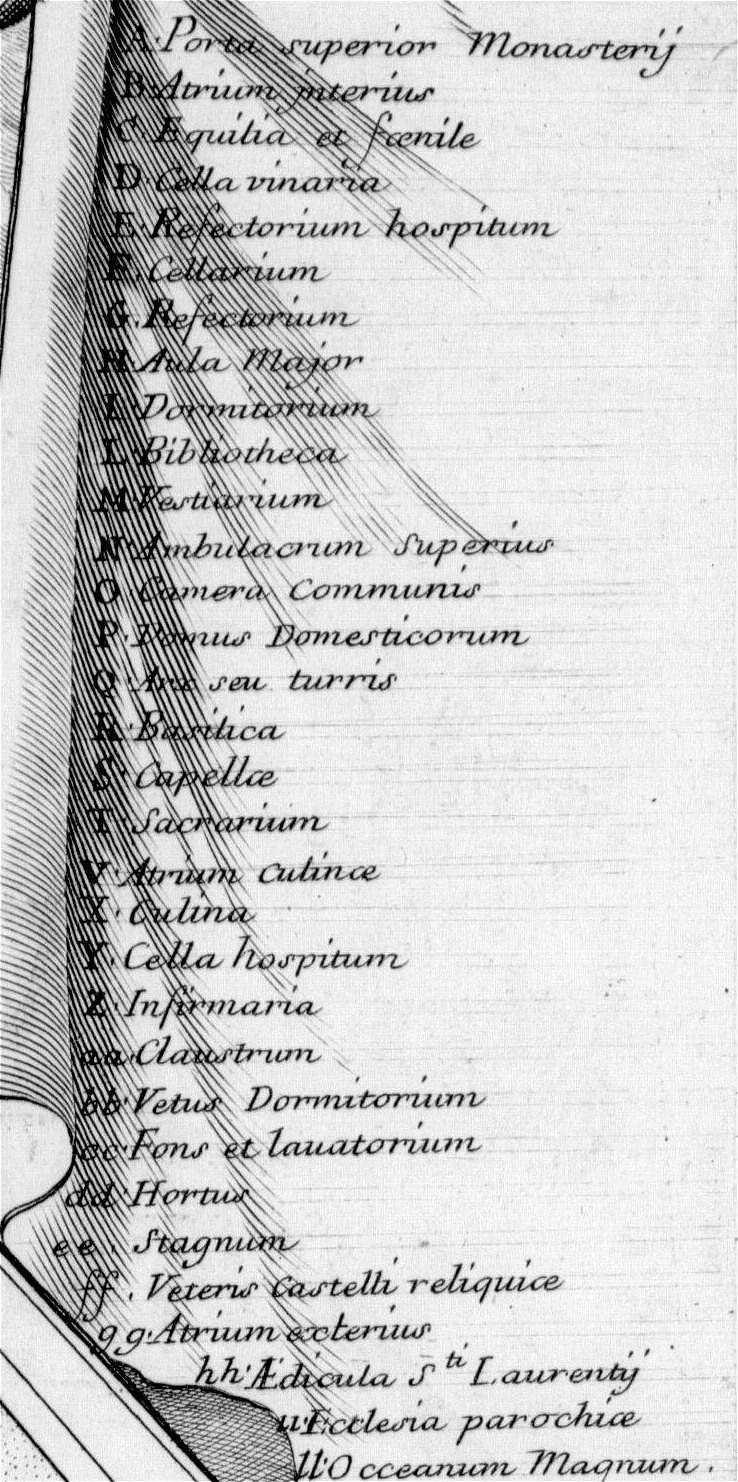

This model was made according to the plan set out below :

In bold, the actual ruins. All the outbuildings have gone.

Plan taken from Canon Eliès : Plougonvelin, Saint-Mathieu de Fine Terre, Le Soc ed, 1972.

Only rare drawings survive, allowing us to imagine the configuration of the abbey as it was before.

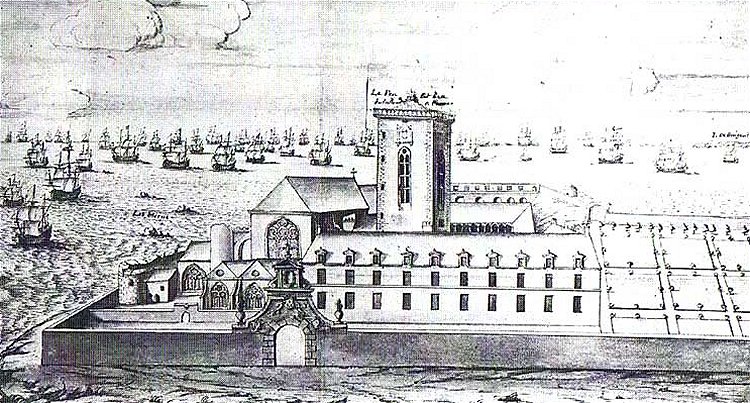

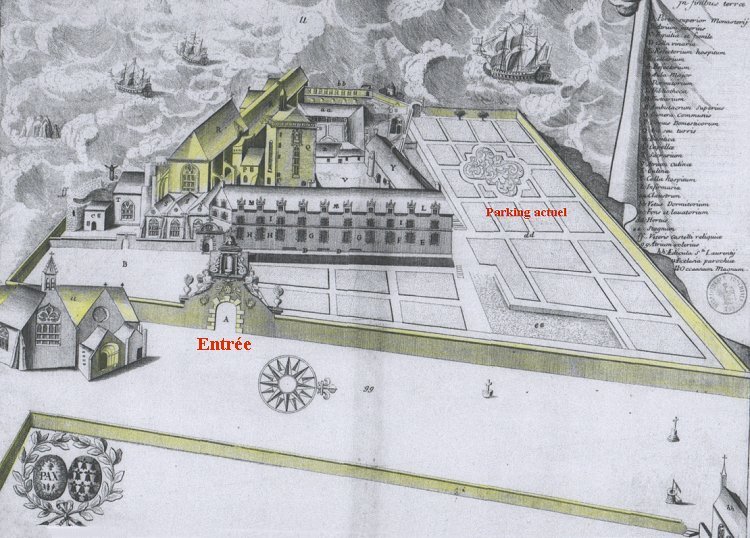

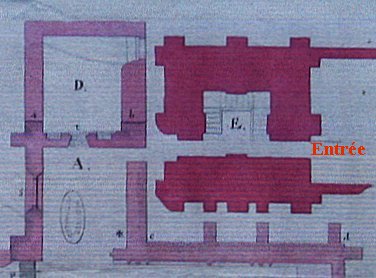

Plan extracted from Profile of Saint-Mathieu Fine-de-Terre by Sieur de La Belle Veüe-Dumains, 1691

National Archives.

The abbey of Saint-Mathieu. Plate n°152 of the Monasticon Gallicanum, dated 1694.

On this engraving, which has a small family resemblance with the previous one,

only a part of the buildings (in yellow) still remains.

Comparing this engraving to the model, we can see that major works were carried out at the end of the 17th century. It is the work of the reformed congregation of Saint-Maur to whom the Parliament of Brittany entrusted the running of the abbey in 1656.

But this renewal was short-lived. The abbey was already in very poor condition, and had been used as a stone quarry in the Revolution years.

During the Restoration, two chapels at the chevet of the abbey church were pulled down to make way for the lighthouse which was inaugurated in 1835. On this occasion, the high tower, which resembles a keep and which overlooked all the other buildings, was reduced by half, so as not to obscure the light beam of the new lighthouse.

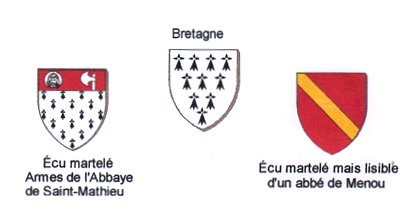

Let's take a look at the entrance porch to the site. It has three coats of arms. In the centre is a reconstruction of the Duke of Brittany's coat of arms and the date 1672. On the left, completely weather-worn, those of the abbey. On the right, those of Abbot Louis du Menou, who from 1658 to 1702 was the promoter of the Maurist revival of the monastery.

© Michel Mauguin.

The Porch.

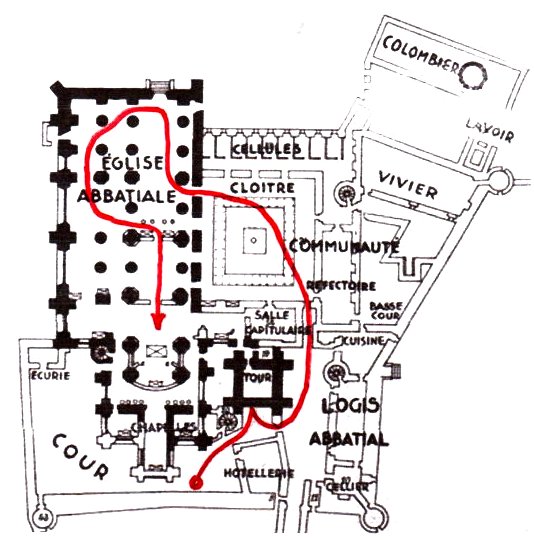

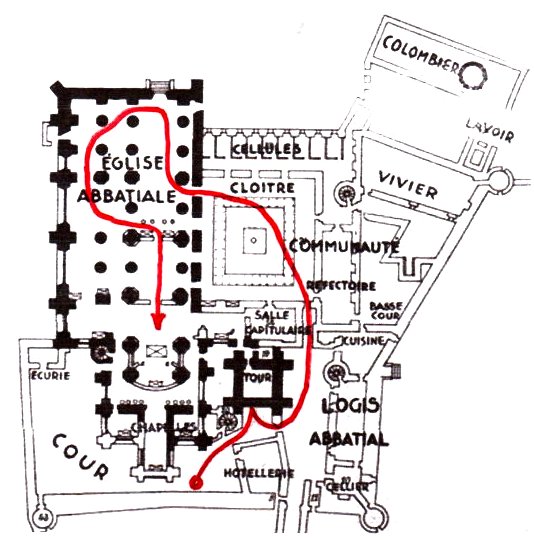

Currently the entrance to the church is through the gutted chevet of the building, which is very unusual and does not help the visitor to understand its configuration. We therefore propose a visit according to an itinerary more respectful to the history of these ruins and the chronology of the different parts of the abbey church. Let's pretend the current access to the church is blocked.

This gives us the 16th century site plan, and consequently the following layout :

- We'll first see

the fortified fire tower

which rises to the right.

- Then the traces of the

medieval monastery buildings

that have been dismantled.

- After, the ruins of

the abbey church

whose multiple modifications must be contemplated to fully appreciate the intensity of activity and change over the years.

- Finally, what remains of the

large Maurist building

which replaced the guest area and which was found during archaeological excavations.

A visit to the Abbey Museum is then a must. It will allow us to retrace the history of the abbey and to understand the importance of the whole site.

-1- The fortified fire tower.

Northeast corner of the tower.

This massive building is probably the oldest of the whole abbey. It used to be much taller than the church. Its large buttresses, its openings far from the ground, make one think of a fortified keep from the 11th century and it is quite possible that it was a refuge during the attacks the site suffered during the Middle Ages.

Just look at the facade in front of you and you'll see that the openings have undergone many changes over the centuries. A large archway, for example, has been filled in. Windows have been enlarged and then partially refilled. We can guess that these changes are due to strategic considerations.

Above the entrance corridor, we can clearly see that a passage once joined the building to a construction that must have existed where we are now.

The tower also served as a bell tower for the abbey church, as 7 beautiful bells were taken as booty in 1295,

during an English raid.

Canon Eliès : « Plougonvelin, Saint-Mathieu de Fine-Terre », Les Amis de St-Mathieu Ed., 1985.

But it was also used as a watchtower thanks to its roof rack and above all as a lighthouse to aid navigation.

A fire permanently lit at the top of the point

Dom Simon Le Tort : « There is still standing in the centre the keep or high square tower at the top of which is a lantern in which a torch used to burn as a guide for the sailors ; and for the maintenance of this lantern, the abbey could originally claim bounty from the ships wrecked up on the coast ; but the procureurs du Roy and the officers of the Admiralty, confiscated this right in the name of the King and that is why the lantern no longer shines. » Compendium historae abbatiæ sancti Matthæi in finibus terrarum, 1681

in order to alert friendly vessels of the rocks which litter the end of the Four Channel.

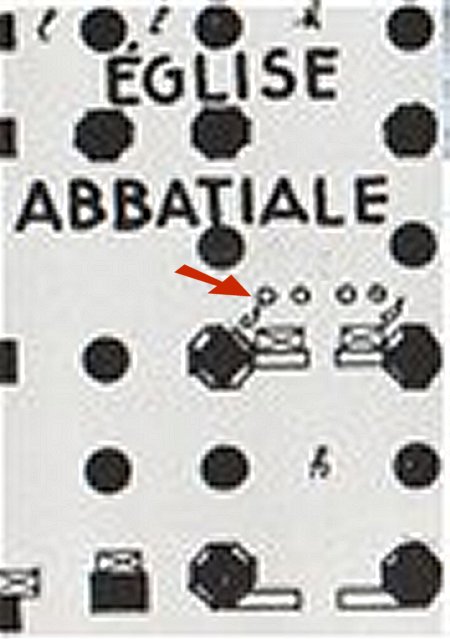

Detail of plate n°152 of the Monasticon Gallicanum.

Initially, it was the Benedictine monks who were in charge of maintaining the blaze. Around 1630, the breaking and anchoring rights that compensated for this burden for their community

were taken away from them

This measure is understandable as even if they were monks , the fact that those who maintained the fire were also the beneficiaries of possible shipwrecks must had fuelled many rumours

and attributed by Louis XIII to Cardinal de Richelieu

.

Subsequently the French Royal Navy was given the task of maintaining the fire.

On the engraving, we see that this one was sheltered by a lantern. Storms and fire hazards for the roof of the nearby church necessitated the construction of this shelter. Subsequently, the wood fire was replaced by

« lanterns »

Prosper Levot :« In 1693, a glass cage was installed at the top of the tower containing three rows of lanterns : two of six and one of three. » L’abbaye Saint-Mathieu de Fine-Terre ou de Saint-Matthieu (Finistère), 1874

.

These fish oil lamps gave off smoke and blackened the windows, raising doubts about their effectiveness. We also have information that the lantern was knocked down in 1750 by a storm.

The demolished part of the building had four high windows that appear in the engravings. It is therefore probably at this level that the tower could have been used as a bell tower.

Let's get inside this massive fortification.

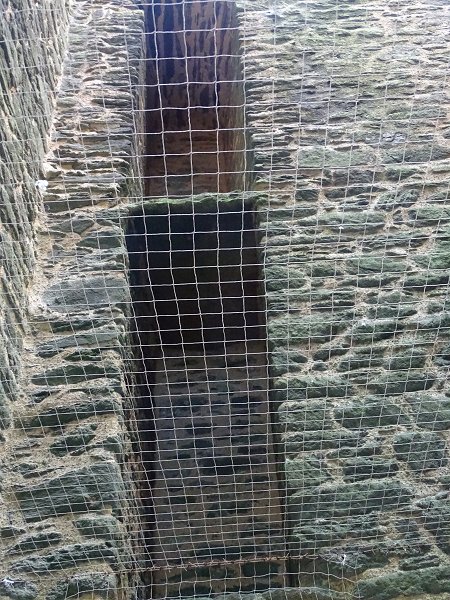

The entrance corridor to the tower runs through a 1.5-meter-thick wall.

At the back, on the west side, we see a passage that allows access to the church.

This exit is overhung in the floors

by two other walled passages.

Observation of the interior of the building is difficult because it is dark and a safety net that has been placed above the visitors obscures the view somewhat.

On the north face there is an old window, also walled up, but breched by an oculus to let in daylight.

Inside the tower, north face.

On the same level, on the east side, above the entrance, there is an access to an identical window, also walled up, and preceded by a few steps. As seen from the outside, this former window was used as a passageway to a building that no longer exists.

Inside the tower, east side.

At the top, there are traces of two old floors

and a window with seats.

East side: The third floor window with seats

© Photo Armand Breton, Les Amis de St-Mathieu

In the northeast corner, door frames overlook the void. Curiously, they do not face the outside. Traces of the old floors are located under these openings.

Northeast corner.

How could one access all these levels and the ones that were demolished?

We look in vain for the trace of the outside spiral staircase which on the plan is to the left of the entrance. Actually, there is a spiral staircase, but it's hidden in the northeast corner.

Start of the spiral staircase at the second floor level

© Photo Armand Breton, Les Amis de St-Mathieu

The spiral staircase at the next floor

© Photo Armand Breton, Les Amis de St-Mathieu

From the top of the lighthouse, you can see its culmination at the current top of the tower.

And it was through doors that access was gained, but only from the second floor.

So how did they get to that second floor?

A plan from 1775 shows that opposite the entrance, against the west wall, there are the first steps of a staircase which are butted up against the north wall and then lead on to the east wall, and finally to the walled door above the entrance.

Choquet du Lindu: Plan of the Church of the Reverend Benedictine Fathers of the

Community of St. Matthew. National Archives, detail, 1775

In the buttress, there are the remnants

of a side staircase leading over the entrance.

Inside the tower, on the south face

There are remnants of a gallery

leading to the walled window on the west side.

The mark of the side staircase continues up the buttress of the west face and leads to the second floor. So that's how access to the spiral staircase leading to the upper floors was gained.

It is likely that this complicated layout was devised for reasons of defence. The side wooden staircase had probably replaced a simple ladder that was lifted from a hatch in the second-floor in case of attack. The only access to the upper floors via the narrow spiral staircase was then easy to defend.

An archaeological excavation in the small area of the tower's ground may provide more information about the building's past.

But let's go back outside to the east face.

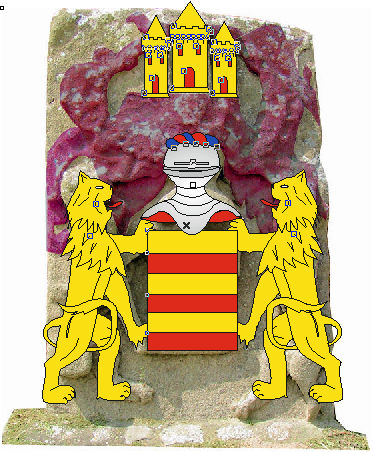

In the engraving of the Monasticon Gallicanum one may have noticed a coat of arms above a window. It was dismantled in the 19th century when the upper part of the tower was demolished. The visitor can see it today at the foot of the building.

Armoured stone from the top of the fire tower.

Although this coat of arms, which was once painted in bright colours, is now very faded, we can guess the horizontal bands, the fasces, of the coat of arms of the Du Chastel, the powerful lords of Trémazan who always claimed the creation of the abbey. According to the heraldist Michel Mauguin, it is a shield « fessworked of six pieces Or and Gules, supported by two lions, surmounted by a helmet adorned with

The lambrequins were thick pieces of leather that protected the neck of knights in armour

lambrequins

and crowned with three towers ».

Draft restitution of the shield of Du Chastel

fascé d'or et de gueules = with horizontal gold and red stripes

© Michel Mauguin, 2020

These coats of arms, which dominated the whole abbey, recalled its creation by the Du Chastel family and fully displayed the anteriority and the omnipotence of seigneurial power over religious power.

We'll come back to this place at the end of the tour.

See below on Youtube the short video of Armand Breton on the fire tower:

( Turn on the sound )

Back to the visit of the whole abbey

-2- The remains of the dismantled buildings of the medieval monastery.

The north and west sides of the tower retain very few openings.

And we can only guess where the walled passages were on the west side that gave access to the church, the chapter house, and also to a small prison no longer there, located between the tower and the chapter house building.

The prison and the chapter house

which was topped by two storeys

extended the gutted transept behind the tower.

Now let's take a look at the space in the direction of the small squat lighthouse.

The corner of the walls located at the red marker is shown on the plan below.

These two sections are all that remain of the abbot's residence.

The land, which is now grass, was adorned with buildings in the 16th century. The abbot's residence, a monastic inn for pilgrims, a prison, the building of the chapter house, kitchens and a refectory, a cloister lined with small columns and a building housing the monks' cells, a fishpond, a dovecote... All these constructions, considered as national property, were sold during the Revolution to a contractor of Le Conquet named Budoc Provost who dismantled them to sell off the stones. Only the abbey church and the fire tower were excluded from this sale.

The scattered remains of the monastery can be found today in many 19th century buildings in the area.

On the 16th century plan, we see that the abbey was surrounded by a rampart. At the back of this area, there is still a section of this thick wall.

The rampart has arrow slits and semi-buried holes for the bowmen.

Each truncated walled window has a window-seat above.

At this point the rampart also formed the west wall of the building where the monks' cells were located. The present land, probably encumbered by rubble, is much higher than the ground floor of the building. The holes for bowmen were therefore on the ground floor and the now walled-up windows of the monks' cells were on the second floor.

The junction of the gable of this monks' building with the north wall of the church is clearly visible, as well as the trace of the second floor and the slope of the roof :

These remains are the only evidence of a building here. And on the site of the small lighthouse, there is today no indication that a cloister existed there for centuries.

Without a doubt, if one day archaeological excavations were to be carried out, we would find many substructions under a heap of rubble.

Back to the visit of the whole abbey

-3- The abbey church.

Enter the abbey church through one of the side doors from the cloister site. There are two reasons for this.

Firstly because the main entrance portal to the west of the nave is no longer accessible from outside. It is still accessible behind the rampart via the semaphore's military land, which is the property of the French Navy and forbidden to the public.

It was through these side doors that the monks used to walk to take part in the services.

So let's follow them.

Even in ruins, the church is of course the main building of the abbey. To fully understand its structures, it is essential to carefully observe the following plan :

Through this door, the monks had direct access to the stalls reserved for them in the liturgical choir.

Against the columns : remains of the wall of the liturgical choir.

We will see later that this choir obstructing the nave did not always exist.

Let's head right towards the main gate of the church.

Main entrance to the nave.

The inner arch is semicircular. The outer arch, more original, is trilobal.

On the outside, three arches precede the trilobal arch

© Photo Armand Breton, Les Amis de St-Mathieu

Like the gate, a secondary side door, now closed by a grille, opens out onto the military zone.

From Romanesque to Gothic style :

The north side aisle is narrow and dark. High windows are semi-circular. Their base has sometimes been walled up.

North side, west gable window.

The north wall has areas where small stones have been laid out

in spike-shaped or fishbone-shaped pattern.

The stones are said to be « spike-shaped » when they are arranged at a 45° angle, or « fishbone-shaped » if two superimposed lines are reversed. These arrangements are not specific to medieval constructions : many have been made since then, but for decorative purposes, which is not the case in Saint-Mathieu

According to some specialists, this construction method, which is intended to make up different levels in places, is typically Romanesque. It is still found on the west wall of the south wing of the transept :

These are the remains of the first stone church.

This part of the building surely dates back to the second quarter of the 11th century. The church was then entirely Romanesque and almost as long as it is today. You must imagine it being even taller than now and not arched. However, it must have been dark inside as only the narrow windows on the side of the nave provided a glimpse of daylight.

It was the time when the first pilgrims came to pray in numbers at the foot of the recently relics attributed to the apostle Saint Matthew. the monks quickly realized that the church needed to be modified and enlarged.

The first modification

The four pillars of the first two bays of the nave are made of limestone. It is easy to recognize this, as the stone is weather-worn. Their capitals are in the Romanesque style.

1st North pillar : the arches rest on elegant Romanesque capitals

decorated with hooks imitating young fern shoots.

Interestingly the first arches that these pillars support are not Romanesque. The semi-circular arches they were supposed to support were replaced by third-point arches.

We are in the end of the 11th century. It is a time when the Duke of Normandy, William the Conqueror, was preparating to invade England. It is also a time of one of the great pilgrimages, and preparation for the first crusade. In architecture, Romanesque art was gradually abandoned in favour of Ogival art.

On the north wall of the church

one of the ancient Romanesque doors to the cloister has been walled up.

The coat of arms signing the new bow could not be identified.

Let's take a look at the south side of the church.

It is confusing because it was originally as narrow as the north side of the nave. Behind the same arcades as those in front, it was closed off by a South wall which no longer exists and which was extended to the transept.

On the west gable of the church we can very clearly see

the traces of this ghost wall and a first roof.

However, it was important for the monks to maintain the influx of pilgrims while the work in the nave continued. Of course, the services always had to be celebrated. So, we can easily understand the need to create a new place of workship.

To enlarge the building, the monks took advantage of the land that extended towards the sea, south of the abbey. They built a new structure with a gabled roof, parallel to the Romanesque church.

The new building ( red marker ) seen from the lighthouse.

Its length corresponds exactly to that

of the first two bays of the nave.

- Halt ! Stop everything ! What's this old-fashioned construction you are building ?

This is probably what the monks must have heard, in perhaps even more crude language, when they were in the midst of renovation work.

In the nave, the replacement of the old Romanesque arches with pointed arches was already well advanced.

But from the third span on, we see that the architecture has radically changed. The last south limestone pillar of the nave supports an unfinished Romanesque capital :

Second pillar of the nave, south side.

In the middle of construction, the stonemason

suddenly abandoned the hook decoration.

Then we move on to octagonal and round granite pillars.

South side : last limestone pillar,

then alternating round or octagonal granite pillars

The bows are higher and less massive. The grey shale stones that make them up and those on the wall above them are smaller and of different origin. We are now fully in the Ogival period where height and lightness were compulsory.

In front of the north wall, with hight round-headed windows, new granite pillars are topped by a capital with simple mouldings soberly decorated with scrolls :

Octagonal pillar and Gothic arch on the north side

making the end of the beautiful Romanesque capitals.

Let's take a look at the front of the gate.

View from the west gable. Above the semi-circular window

there is a difference in construction

Clearly, the upper part of the west gable has been split to accommodate a lower frame. And the north wall shows that it has been levelled off to the height of its mullioned windows.

View from outside : in the foreground, the North wall with its flattened top.

Behind it, the arcades have been raised.

Changes also in the South extension

As the new building was not big enough, the monks built two new extensions perpendicular to the nave, more or less copied of the south wing of the transept. In the photo taken from the top of the lighthouse, the triangular apex of the three contiguous gables is characteristic.

The west wall of each of these extensions was maintained by a fully Gothic perpendicular arcade supported by new granite pillars.

In the new south wall, the extensions

had several semi-circular exits that were walled up.

The ghost wall of the south aisle was replaced by a new series of Gothic arches, now broken.

For such a small community, this monumental work must have taken decades. During the works, techniques would have been improving and travelling monks arriving from other abbeys, who had participated in other workcamps, would have certainly provided additional skills. It is therefore not surprising to see different architectural techniques cohabiting in the same part of the current ruins.

However, according to

Yves-Pascal Castel,

Yves-Pascal Castel: « L'abbaye Saint-Mathieu revisitée »

in Saint Mathieu de Fine-Terre, proceedings of the colloquium of September 1994.

this brutal change in the transformation of the church is rather due to a political cause.

Duke Conan IV, under the threat of war with the King of England Henry II Plantagenet, left the English to rule Brittany from 1158 until his death in 1168. And the Breton project manager of the building site was replaced by an Englishman who imposed the fully Gothic architecture that he knew so well. This English domination really ceased only in 1202 when King Philip-Augustus confiscated all the property owned in France by the English king John the Landless.

Boreholes conducted by Michel Le Goffic at the foot of two pillars of the South collateral revealed a Louis VIII silver coin dated back to the period 1223 to 1226. But this to date the collateral is not unreliable because the coin was found in soil disturbed by several burials.

Let us take a closer look at what remains of the liturgical choir.

A wall was erected on each side of the nave between two consecutive pillars.

It enveloped them and integrated perfectly into their construction.

It can therefore be affirmed that the liturgical choir was originally contemporary to the construction of these pillars.

On either side of the nave, along these columns, there is a projection or a small column. This suggests that a transverse bulkhead must have been supported by it. This is the rood screen mentioned above in the 16th century plan of the church.

Detail of Canon Eliès' plan.

In the Middle Ages, the faithful attended services standing. The liturgical choir thus obstructed the nave, leaving only a narrow central passage free, as was customary.

It is difficult to understand today the need for such a construction, which prevented the public from seeing the altar.

But we're in an abbey. Only the monks, out of sight in the liturgical choir, had stalls equipped with mercy seats that allowed them to sit discreetly. And they had to attend several services a day.

So priority was given to the monks.

One can understand the usefulness of the enlargement of the south side from which the altar was partially visible.

Let us observe the composition of the south wall of the liturgical choir.

This very thick wall was destroyed and then summarily repaired. Perhaps it was voluntary demolished as it is hard to see what other cause could have brought such an edifice. So, it appears that at one moment, the liturgical choir was torn down or destroyed, only to be rebuilt at a later date. Destruction during a looting? Or simply a difference of opinion between different abbots ?

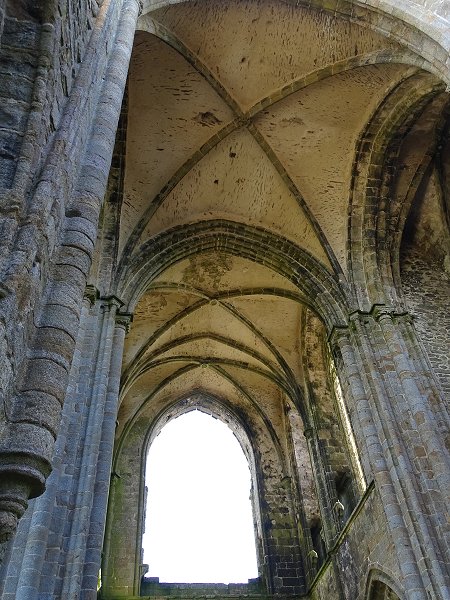

The transept

It is much taller than the nave.

View from the nave towards the choir.

At the crossing of the transept, the building suddenly takes height.

The transept and the chevet of the church culminate at 18 m

We're coming into the sacred part of the building. Its Ogival architecture becomes different from that of the nave.

View of the transept, from North to South.

You can see the shape of its two successive roofs.

The north wing, in the foreground, is open.

We can only make out the mark of its west wall.

The transept of the church has been considerably modified. All that remains of its north wing is a section of wall and traces of damage. The large ogival window on the left illuminated a passageway to the prison and the fire tower. High cross vaults still overhang the central part of the transept. At the end, the south wing has remained Romanesque.

The Apse

The architecture of the traditional choir that occupies the apse is particularly well preserved.

Choir's ribbed voult.

Arches and ribs are supported by small columns.

The filling and stained glass of the master-window was destroyed,

probably during the construction of the lighthouse.

View of the nave from the master glass window

© Photo Armand Breton, Les Amis de St-Mathieu

This opening, now gaping, and the twin side windows

flooded the choir with the coloured light with their stained-glass windows.

Outside, flying buttresses reinforce the walls.

Twin windows on the north side.

These high windows are very elaborate. The fine columns are inserted, either in the walls or in composite pillars, which are themselves engaged.

Everything has been thought out to translate a surge of faith towards heaven.

Here we are at the crossroads of the 13th and 14th centuries, at the height of Gothic art.

The ambulatory and adjoining chapels

The north side of the building runs east in a straight line. Beyond the transept, it is extended by an ambulatory that goes around the choir. This way we can reach the South collateral.

The north side and at the end the ambulatury

leading to the only surviving chapel.

In the South, the ambulatory that leads to the collateral.

On the left, behind a grille, you can see the start

of a spiral staircase leading to the top of the building.

Three little apses occupied by chapels once extended the flat apse of the church. But due to the construction of the lighthouse, only the north one survived.

The North Chapel

© Photo Armand Breton, Les Amis de St-Mathieu

The North Chapel dedicated to Saint Andrew.

The filling and stained glass windows of its large bay were also destroyed.

Its altar still remains, while that of the choir has disappeared.

As soon as you leave the choir through the gap in the wall,

you find yourself outside, where the central chapel has been destroyed. It was two bays long. This chapel was dedicated to Our Lady of Loreto. A tomb is embedded in the burial wall of its first bay.

The Kersanton tomb of Guillaume de Kerlec'h.

Yves-Pascal Castel reminds us that this abbot directed the abbey from 1430 to 1462. He details the sculptures of the tomb

in the republished book,

Yves-Pascal Castel: « L'abbaye Saint-Mathieu revisitée »

in Saint Mathieu de Fine-Terre, proceedings of the colloquium of September 1994.

available at the Abbey Museum.

The broken archway marked

the second bay of the central chapel.

The south chapel, dedicated to Saint Margaret, no longer exists. It was locating between the church and the lighthouse.

The walls of the church still bear the marks of its destruction.

One wonders why the architect of the lighthouse demolished two chapels of the church when this new construction could have been erected a few meters to the east.

But at the beginning of the 19th century, we didn't have the same notion of heritage as today. The abbey church had been in ruins for almost a hundred years. It could no longer be of any use since the monastery buildings had been destroyed. For security reasons, long before the Revolution, services were only held in the nearby Chapel of Our Lady of Grace, which was the parish church. And the ruins were no longer considered of any value. They were unattractive, even frightening.

On the other hand, the lighthouse represented modernity, vigilance and rescue for the sailors. Utility outweighed futility.

Let's now continue our visit towards the sea to observe, from the outside, what we saw inside the building.

The difference in construction between the lower and upper part of the choir is clearly visible in the buttresses and windows. At the bottom, the large triple-lobed and triple-arched windows of the choir mimic the architecture of the west main entrance of the nave. The geminated windows of the elevation were constructed a century later.

There is also a low door leading to the ambulatory and the spiral staircase that leads to the top of the church. However, keep in mind that we are on debris-filled ground, much higher than the ground floor of the church. Behind the picnic tables, the east wall shows traces of a large walled up Romanesque window that illuminated the south wing of the transept.

Next to this is the alignment of the South wing with two extensions and, at the very end, the first building extending the South side.

We can recognize the different periods

of the construction of the windows by their architecture

© Photo Armand Breton, Les Amis de St-Mathieu

Visitors are always intrigued by the surprising « tower of Pizza » inclination of the two gable extensions. It really feels like they're about to fall down. Specialists propose various hypotheses for them leaning towards the sea : too much lateral pressure from the old slate roof, insufficiently contained by the first buttresses. Or soil compaction due to wave pounding in the underlying sea caves. However, the gables have survived many centuries and will undoubtedly continue to so, long after we have gone.

South Collateral : 3rd extension against the south wing of the transept

On the wall of the transept, there is an oblique trace of an old roof space

that may have belonged to the first Romanesque church This trace indicates that before the construction of the two gables, the nave and the south collateral had a roof sloping towards the sea

Similar traces, even including slate debris, extend to the top of the building. The difficulty is to assign a chronology to these successive alterations of the roof.

© Photos Armand Breton, Les Amis de St-Mathieu

South Collateral : 2nd extension

South side : 1st extension. Near the buttress,

a semi-circular door opened onto the outside.

As on the west façade, the Romanesque window is partially walled in.

On the left is the end of the rampart extending the façade

Back to the visit of the whole abbey

We will end our visit by returning to the fire tower to discover what remains of the great maurist building that was partially hidden on the engravings but still in the archives.

4- The great Maurist building that disappeared.

When in 1656 the Parliament of Brittany entrusted the St-Mathieu's Abbey to the reformed Benedictine congregation of Saint-Maur, the state of the monastic buildings was deplorable. Focusing all their efforts on the work in the abbey church and also probably due to a lack of sufficient staff, the monks, who were only two at that time, had long ago abandoned the maintenance of the monastic buildings, particularly, the oldest one that housed their cells located along the western rampart, and had become a slum.

The new occupants therefore decided to erect a new monastic building.

But although it was more recent than the other constructions of the monastery, it did not escape the general demolition undertaken during the Revolution.

What was in it?

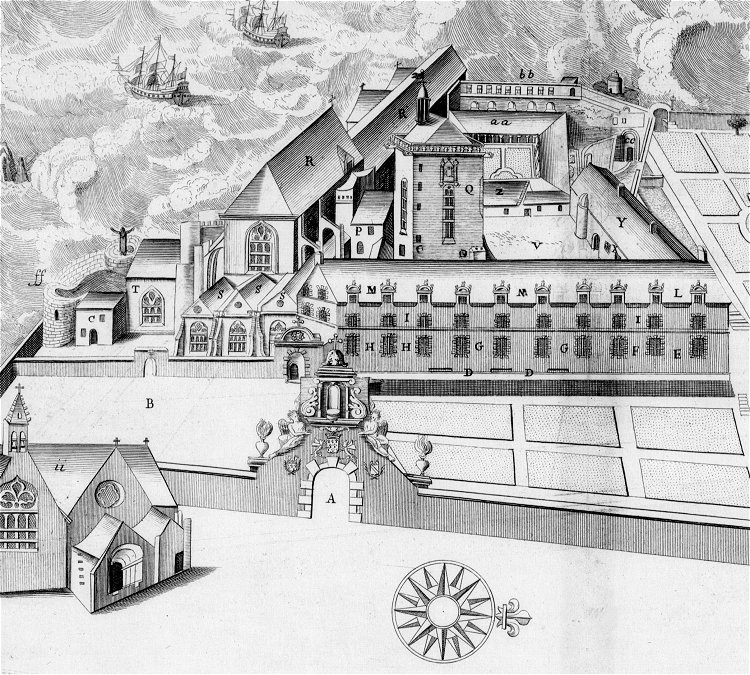

Let's extract from the archives the following rider's view taken from the Monasticon Gallicanum dating from the time of King Louis XIV.

Capital letters arranged throughout the engraving refer to the Latin key.

This is summarized in the following figure :

Explanatory figure created by Les Amis de St-Mathieu.

All that remains of the building is a long platform and the bases of the 10 windows ; two of them have been incorporated into the gable of the museum.

It was thanks to archaeological excavations in the raised strip preceding the tower that this platform was uncovered. And, the icing on the cake, the start of a staircase leading to a cellar was also discovered.

Let's go down this staircase now open to the public :

The cellar of the Maurist monastery is a long-vaulted room, lit by two semi-buried windows facing east. Fairly damp, it has been partially covered with a raised floor to ensure the safety of visitors. The association Les Amis de Saint-Mathieu has temporarily installed easels with explanatory panels. But one can imagine that not only food reserves but also a few carefully chosen barrels of wine were piled up there, in a constant temperature conducive to their conservation.

Mass wine, of course. We are speaking about monks !

So comes the end of this long visit of an exceptional heritage. All you have to do now is project yourself back in time wandering those damp dark corridors in prayer. Don't forget, whatever you do, to visit the Abbey Museum and its superb model of the site.

The Museum of St-Matthew's Abbey.

Thanks to Maria Kermanach for her help and her lecture on the fire tower at the colloquium organized by Les Amis de Saint-Mathieu in September 2019.

Thanks to Glyn Orpwood who reread this text and modified the English version.

Thanks also to Armand Breton for his photos, heraldist Michel Mauguin, historian Jean-Yves Eveillard and Patrick Prunier, president of the Friends of Saint-Mathieu for their help and loan of documents.

***

Read more

Are available at the Abbey Museum :