If you don't have time to read all this page, you can perhaps listen to in French a summary of it :

Plug in the sound and find here the story of this engraved stele

as well as many other elements of our heritage on the website Voix du Patrimoine.

Access :

The Musée du Ponant is located in the centre of St-Renan, at 16 rue St Mathieu, at the top of the Place du Vieux Marché.

See our page onle Musée du Ponant

Groups : welcome all year round by appointment on 02 98 32 44 94

Parking: in front of the neighbouring cinema.

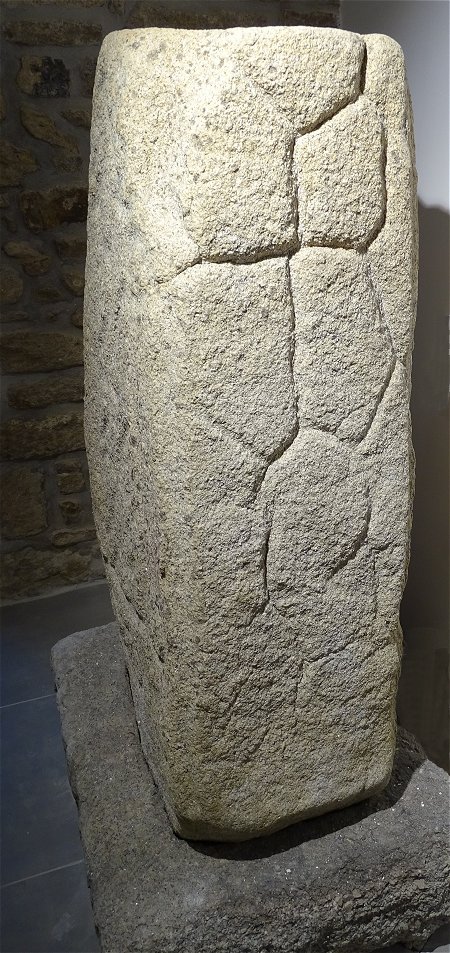

The stele is visible as soon as you enter the museum. It is a trunk of a quadrangular pyramid with a height of 1.28m, carved in a fine-grained granite with two micas. With a thickness of 0.38m, it is 0.66m wide at the base and 0.35m at the top. Its sides are differently chamfered, better worked on one side than the other. The bevelled base is very short: only about twenty centimetres high. This stele has enigmatic engravings on two of its faces.

A chance discovery

The stone was laying the engraved face against the ground and, together with another ungraved stele, constituted the threshold of the ruined lean-to of an old farm in the commune of Brélès. It was discovered in 2001 when the new owner wanted to recover the stones in order to restore a fence wall. Local historian Yves Chevillotte and departmental archaeologist Michel Le Goffic were informed and studied the engravings. This study was published in 2003 by the Société Archéologique du Finistère in Volume 131 of its Bulletin, pages 63 to 70. Thereafter, the engraved stone remained outside, exposed to the elements, and the Musée du Ponant, in order to safeguard it, acquired it in 2017. The second stele, of very classic construction, was erected by the owner along his driveway. Located inside a private property, it is not exposed to the public.

The main engraved face

The engravings only appear well in grazing light.

The upper right corner of the main face has been chipped.

A granite pedestal has been made by the museum

to hold the stone vertically and secure it

for the public.

Photos Y.L. 2019 ©

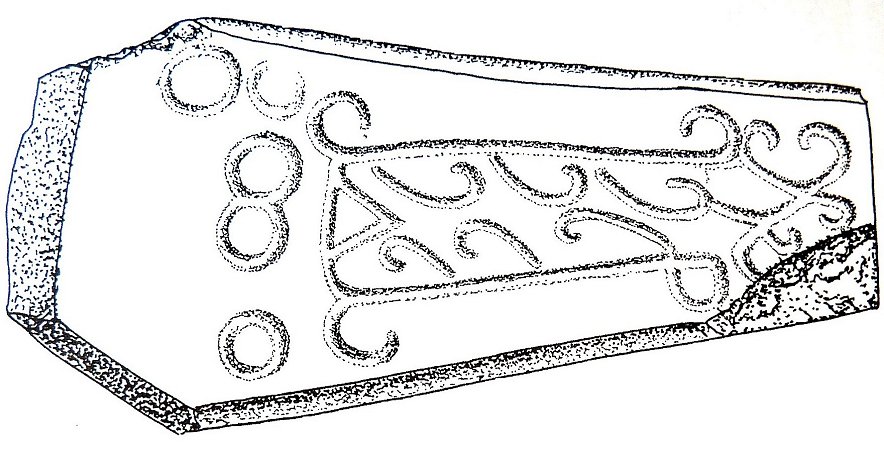

The engravings were carved into a flat surface of the stone. The grooves, 2 cm wide, are about 3 mm deep. Their bottom is rounded in a U-shape. There are three areas :

-

At the bottom left, a circle is partially cut into by the size of the bevelled stele. This circle is surmounted by four other horizontally aligned, two of which are tangent. It should be noted that those on the left have been also affected by the size of the stone.

-

The central part is made up of a kind of rectangular cartouche in which six hooks have been engraved. The two long sides of the cartouche end in outwardly curved hooks. They are therefore symmetrically opposed and are connected to each other at their base by a groove supporting a triangle pointing upwards. The six hooks oppose each other two by two in an inverted position, their rounded ends pointing towards the sides of the cartouche. There is no groove to close the upper part of the cartouche.

-

Above the central part has been engraved a kind of X with curved ends, which extends into two grooves, one of which touches a hook and the other goes towards the chipped angle of the stone.

The right face :

The stele being thin, its sides are less wide than the main face. The right side of the previous one has even more enigmatic engravings.

On this face, we see that the size of the stonehas truncated the engravings at the top and at the left.

Photo Y.L. 2019 ©

The grooves are both narrower and deeper than those on the main face. Their section is in a V-shape. They follow a slight natural crack in the stone. They form a network with irregular meshes, the edges of which would have been destroyed by a later size. The engravings on this side have not yet been explained.

Below the grooves, a large space is not engraved. Then the stone bulges slightly outwards, as if it were the beginning of a large base.

We also see that the right edge is carefully chamfered. The left one is less well worked.

Despite the absence of a thorough study of this side by archaeologists, a close examination already suggests that the stone has a complicated history. One can indeed assume that the engravings of this side are the oldest. And that before being truncated by a first size, they extended further up and to the left. It was probably a large stele that had a significant base now gone. It represented a kind of paving whose elements interlocking at the point may have had a sacred character. We can also imagine that, as on the slab of Saint-Bélec1 (Finistère), the engraved network could have constituted the map of a territory or a plot of land dating back to the Bronze Age. It was much later that it would have been chosen and re-cut. It would therefore have been shortened and its width reduced in order to engrave its main side. Finally, in more recent times, its embase would have been removed. And, cut into a bevel, the stele, that could no longer stand up, could be used as a tombstone.

The other sides

The other two lateral faces of the stele have no ornamentation. The widest side is flat and its surface is well united. On the other side there is a natural crack in the stone and, near the base, some parallel streaks.

The top of the stone, very flat, has not been dug.

On the yard where the stele has been firmly fixed to the stone base

its two unengraved sides were visible.

Photo Y.L. 2018 ©

An exceptional engraved stele

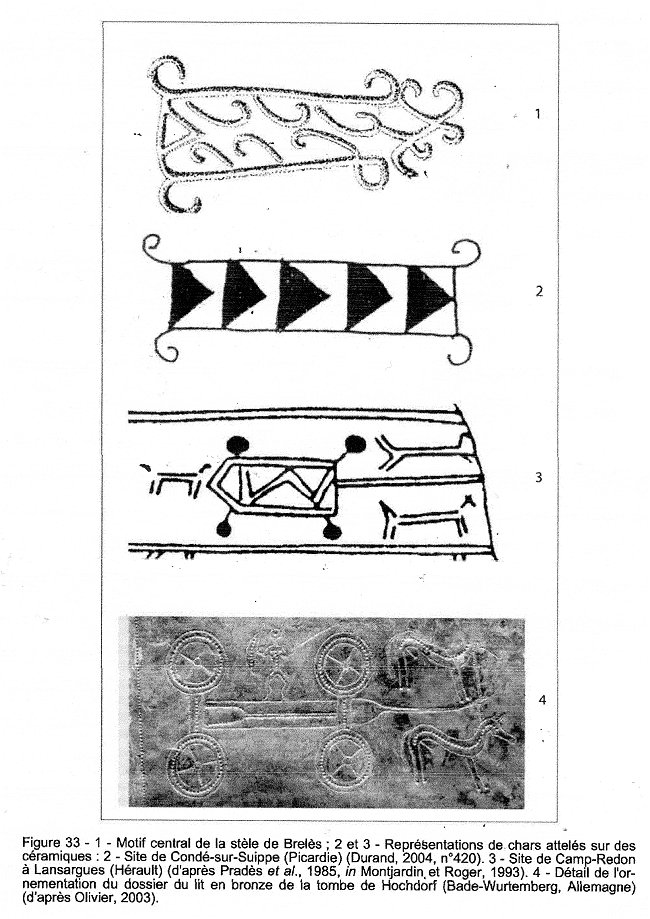

Marie-Yvane Daire, a researcher at the CNRS and a specialist in Armorican steles of the Iron Age, had put forward an interesting hypothesis in 2005. In her book Les stèles de l'âge du fer dans l'ouest de la Gaule p. 76 et 77 she compared the main engraving with other engravings of the same period found in France and Germany. For her, the representation is that of a chariot.

M-Y. Daire: " Les stèles de l'âge du fer dans l'ouest de la Gaule "

© Ed. Centre Régional d'Archéologie d'Alet. 2005

This is confirmed by archaeologist Michel Le Goffic : the main face undoubtedly represents a Celtic chariot. He compared this engraving with another on a rock in Valcamonica, Italy:

In Italy, in the Park of Petroglyphs of Valcamonica

engraving very similar and from the same period represents a chariot pulled by two horses

Main face of the stele.

Drawing by Michel LE GOFFIC and Yves CHEVILLOTTE. BASF volume 131, 2002

The cartouche represents the chariot body. The curved ends are those of the axles. The wheels are dismantled and shown at the rear. And we can clearly distinguish the triangle of the drawbar from the hitch. As for the crossettes, it might be the ties of the side panels.

In this case, why represent a chariot on a stele usually used to indicate the place where a funeral urn was buried?

- Quite simply, replied the archaeologist, because in this place, as in Vix, in the Côte d'Or, there is certainly not only the urn, but also the chariot of a Celtic princely figure.

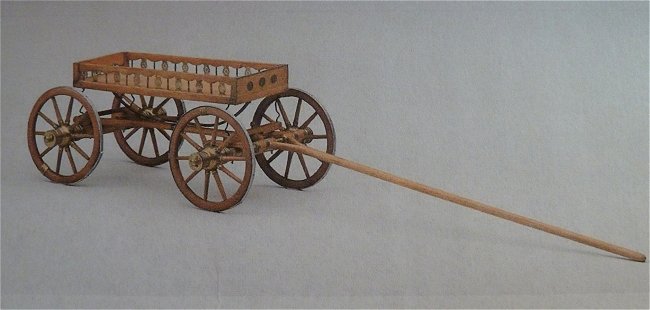

At the Musée du Châtillonnais-Trésor de Vix

a model of the chariot of the princely tomb is reconstructed.

Below, a reconstruction of the tomb where we see the remains of the chariot and the dismantled wheels placed against a wall of the pit.

The explanation is attractive. Unfortunately, as the stele has been moved for the construction of a lean-to, it's not possible to knew its original location.

To this day, no chariot grave has ever been found in Brittany2. Of course, this does not mean that there are none. The lecturer in ancient history Jean-Yves Eveillard thinks that in the absence of a tomb, if the stele represents a chariot, it can also simply evoke the deceased's last journey.

Only further research, such as aerial surveys using drones, may one day give us the key to the enigma.

But already, we can imagine that the place where this stele was originally implanted was not very far from the one where it was found, i.e. at the limit of the domain of the castle of Kergroadès. And since the engravings indicate the presence of a princely tomb, it is interesting to note the permanence of this place of power through two millennia.

In the meantime, the stele of Brélès is indeed a unique monument in France. Visitors and researchers can now come and contemplate and study this engraved stone. It is no longer exposed to the elements and is permanently preserved since the collections of the Musée du Ponant are inalienable.

1- See Sciences et Avenir - La Recherche No. 924, February 2024, as well as the very detailed document onla dalle de Saint-Bélec

published on the INRAP website.

2- Chariot graves are found more in eastern Gaul and beyond the Rhine. The most western one that has been discovered is located at Orval, in the Cotentin peninsula, near Coutances.